The other day I came across a photographer wrestling with the task of capturing his daughter on large format film. He declared, with some modesty given the skill he showed in his images, his attempts a failure. I got the sense he would triumph, however, his declaration being at any rate interim in nature.

Large format photographers are not strangers to difficulty (their medium certainly brings its challenges) nor are they afraid to pursue highly individual whims and visions. It would be easy to dismiss this gentleman as a maverick, and to retire with a sigh, saying something like ‘wrong kit friend, try 35mm and continuous focus for better results’.

Yet an essential part of this photographer’s vision, the look he desires, is 5x4 film. It is a very particular look. And film. Something I fully appreciate in the endeavour is the idea of committing a person’s, nay a loved one’s, visage to film.

So in mulling this over, I set myself the task of expressing what exactly it is that makes a film portrait special. The obvious comparison is with digital, so why choose film instead? The answer I have so far come up with may be no more than a kind of illusion, a piece of analogue nostalgia in an increasingly digital time, a fool’s gold of image making.

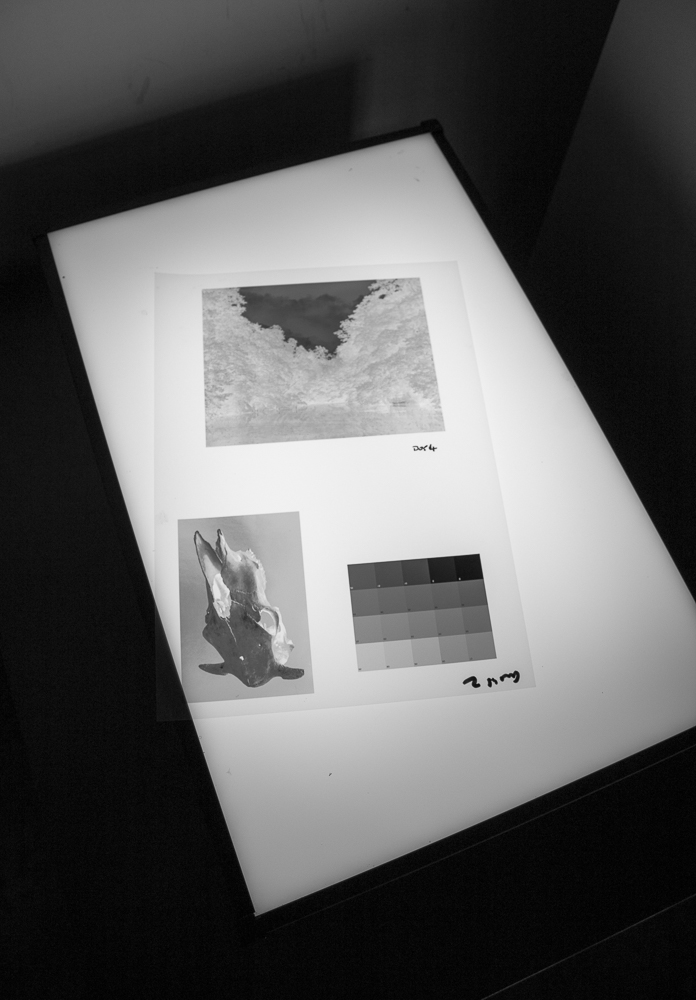

When I think of my own film portraits, I think of the silver gelatin crystals in the negative that have reacted to the light that emanated from the subject. Physical stuff, now tiny grains, that make up an image. A person, etched in a transparent medium that becomes, through the further action of light, a physical photograph to hold in wonderment. When the negative (or the photograph) is in my hand, I hold a token of a causal connection to the being who was once before the camera. I believe semiologists call this kind of relationship between sign and thing represented ‘indexical’. Like footprints in the snow signalling someone’s presence.

Now, digital is of course no less physical than film, hence my talk of fool’s gold. Yet the physicality of digital is, well, just not very physical. Many others have pointed out that images on memory cards and folders on computers are ephemeral. Negatives and prints, by contrast, support the romance of the imagined connection to a person that a portrait fosters. Like a Proustian smell, they are evocative and sensory, and nurture memories. The negative in my fingers is like a little light trap; a special light that really came, indexically, from the person caught within.

My ruminations don’t address the ‘look’ of film as a factor, but I think this isn’t the best place to look for distinctions, at least not on its own. I use and enjoy film simulation presets on my digital shots. These go a long way to imitating film (although not the whole way, for further technical reasons involving focal lengths and formats, old lenses and so on). It is not (just) the look of film that makes it special. It is that and the gravitas of the physical light trap of which I write. Digital pictures image people; film ones bear their imprint.