So what of my experience of using the Intrepid on this trip? And what have I to now add to my original review? Two important things stand out: one is the relative compactness of the camera; the other is that I really hardly noticed the camera at all.

I was conscious of weight and bulk on my trip, a factor that led me to equivocate over whether or not to take the Intrepid. Having solved the tripod issue, I further reduced my load by forsaking my usual Manfrotto backpack. For this generously padded pack, I substituted my thin branded urban rucksack, inside which I placed a light generic camera bag to protect the 5x4. The film holders and darkcloth sat neatly on top. While the fit was a little tight, it did provide the further benefit of being very inconspicuous. With that rucksack on my back, I was truly in urban mode.

To be able to carry a 5x4 camera in such a manner is a real testimony to the design of the Intrepid. My improvised arrangement for China has made me reconsider my normal backpack: I was left with the strong sense that I had previously been carrying more bag than camera. This was a huge plus for me working in an urban environment, but it is of even bigger benefit for those wanting to work in rural and remote locations. If you are not carrying around a lot of film holders or alternative lens choices, weight is not an issue at all.

Setting the camera up and down was a pleasure. I suppose I have now developed enough muscle memory that such actions are smooth and automatic. There really aren’t a lot of adjustments to contend with. For some large format photographers in some situations this will be a problem, but of course, it very much depends on the work you are doing. As I have written before, if you are starting out in 5x4, the Intrepid makes a forgiving companion. It’s a great ‘learning camera’.

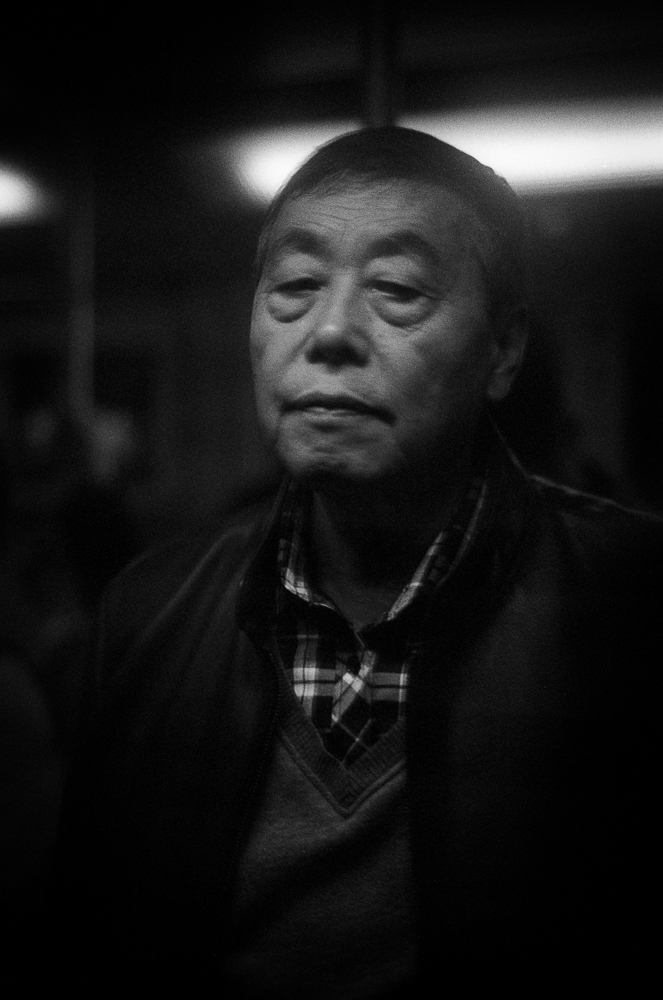

This is what I mean by not noticing the camera. At each location I was fully immersed in making the image, and my control of the camera and exposure really did flow. I’m pleased with the images I made given the time I had. Interestingly, I think I was shooting 5x4 while still somewhat in a street photography mode. I elected more than once to include a passerby, chancing my arm with borderline shutter speeds and using my intuition somewhat for compositional placement (after all, you have gone ‘blind’ once the film holder is inserted). This may be suggestive of further personal work; crucially, for the Intrepid, it shows how it can be used quickly and with ease in public locations.