If you enjoyed my post on the zone system you may be interested in this. I’ve written a longer version for the Intrepid Camera Company, which includes some practical exercises. You can click on the Tweet above, or the button below.

The Large Format Photography Podcast

Happy to report that I’ve been featured on the Large Format Photography Podcast with Andrew Bartram and Simon Forster (as mentioned in my previous post).

A lot of the programme was dedicated to the zone system, with Andrew and I doing our best to improve Simon’s grasp of it. If you’re struggling to work out what the zone system is all about, our musings just might help, as they did for Simon who is still finding his way. Other topics included my large format work, darkroom printing, the idea of fine prints, travel, and the Hypersensitive Photographer’s Podcast.

Do browse the previous episodes, they feature many excellent and interesting photographers. Please click the image above for a link.

Film is HP5+ developed in LC29. Paper is Ilford Multigrade Warmtone Fibre Based.

A portrait and a podcast

Here’s something I’ve been working on recently: a 10x8 portrait of my Dad, Ian Pickup. It’s a contact print on fibre based warmtone paper. I’ve been steadily working away at 10x8, especially on trialling development times to complement my zone system practice in 5x4. The large format adventure is continuing, if slowly, due to the ever present demands of teaching and full-time work.

I have been busy in other ways too. On Tuesday this week I recorded for the Large Format Photography Podcast with Simon Forster and Andrew Bartram. It was great to chat with Simon and Andrew, about the zone system, my work and website, amongst other photography topics. If all is well and Simon and Andrew broadcast the session I’ll share a link in a future post. If you read my zone system post and wanted to know more, our conversation could be a good place to start. I’d also recommend checking out their other podcasts - they have some great guests and there’s lots to learn from other people’s work and experiences in large format. I’ve not got the podcast ‘bug’ in the way other people have, but it certainly is a medium on the up. I enjoyed dipping in and out of podcasts in my downtime.

Intrepid Enlarger launches

The Intrepid Camera company is now selling a kit that converts their 5x4 camera into an enlarger. In their own words:

The Intrepid Enlarger is the ultimate DIY photography tool, converting your 4x5 camera into a darkroom enlarger to make prints from your 4x5, 120, and 35mm negatives. It’s so compact and lightweight it could fit in a coat pocket, use it in your bathroom, darkroom or anywhere you can squeeze into and make dark.

The light source fits to the back of the Intrepid 4x5 (or most other 4x5 cameras) and attaches using the Graflok clips. This plugs into the timer so you can control exposure times which plugs into the mains. Then by mounting the camera to a tripod or copy stand you have yourself a fully functioning darkroom enlarger. It’s that simple!

You can order yours by clicking on the button below. They are currently quoting a lead time of eight weeks.

A handheld spot meter, essential zone system tool.

The zone system in simple terms

The zone system is a method of controlling tone in black and white film photography. It enables the user / photographer to have confidence that tones visualised when the shutter is pressed will be the tones seen in a final print. It involves undertaking careful film exposure and development testing (linked to an individual’s equipment and working habits) and removes the doubts of ‘hope it will come out’ photography.

Read MoreOrléans Cathedral Interior, HP5+ in Perceptol 1+1.

Orléans Cathedral Interior

Ilford HP5+ film developed in Perceptol has a distinctive, open tonality.

'Image quality' redefined

I’d like to propose a counter-term that points us in another direction: image quality. Not, as the Oxford English Dictionary has it, ‘the standard of something as measured against other things of a similar kind’, or even ‘the degree of excellence of something’. No, I mean it in another sense of the same word: ‘a distinctive attribute or characteristic possessed by someone or something.’

Read MoreStill life with brushes on Kodak Ektar 100 5x4 film.

Still life on Kodak Ektar film

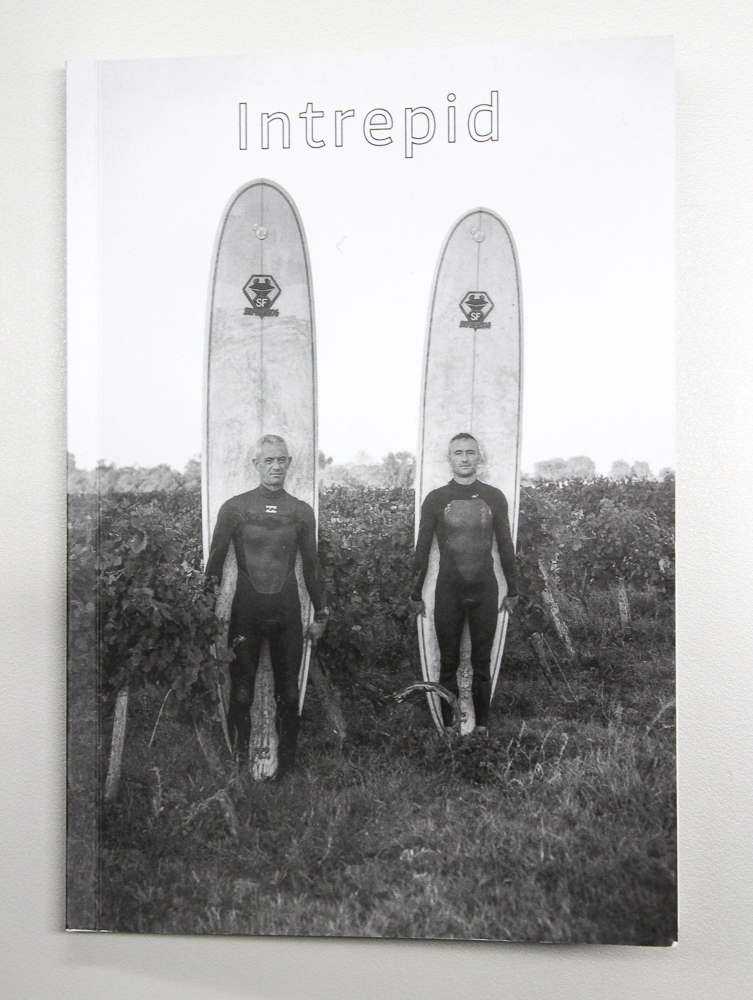

Intrepid Zine Issue 1

Intrepid Zine Issue 1

I often find myself writing about the pleasures of the printed image, and here is a great case in point. Large format camera manufacture Intrepid, no stranger to the pages of this blog, have produced a beautiful little zine. The publication celebrates the work of thirteen photographers who use Intrepids (either 5x4 or 10x8). It is a diverse collection of images that bump up against each other, creating interesting juxtapositions of photographers’ diverse visions.

I am honoured to be the first photographer in the publication. I’ve really enjoyed seeing how others have deployed their cameras, and was struck by just how flexible and wide-ranging a tool a large format camera can be. To point to but some examples: Andrea Koesters presents rich and colourful landscapes, Alex Kryszkiewicz contemplative black and white spaces, Alan Brock scenes of blissful untouched nature; while James Rogers and Pierre Lansac show off their considerable skills in photographing people. The little red sign in Erik Babinski’s rooftop view is a delicious visual punctuation mark.

I can therefore wholeheartedly recommend this little zine (which is a steal at the current price of £7), whether you are looking for inspiration or just trying to wrap your head around what large format photography is about. It is a fine calling card for the medium, and of course Intrepid’s cameras. You can purchase your copy by clicking on the link below.

Alex Burke

Alan Brock

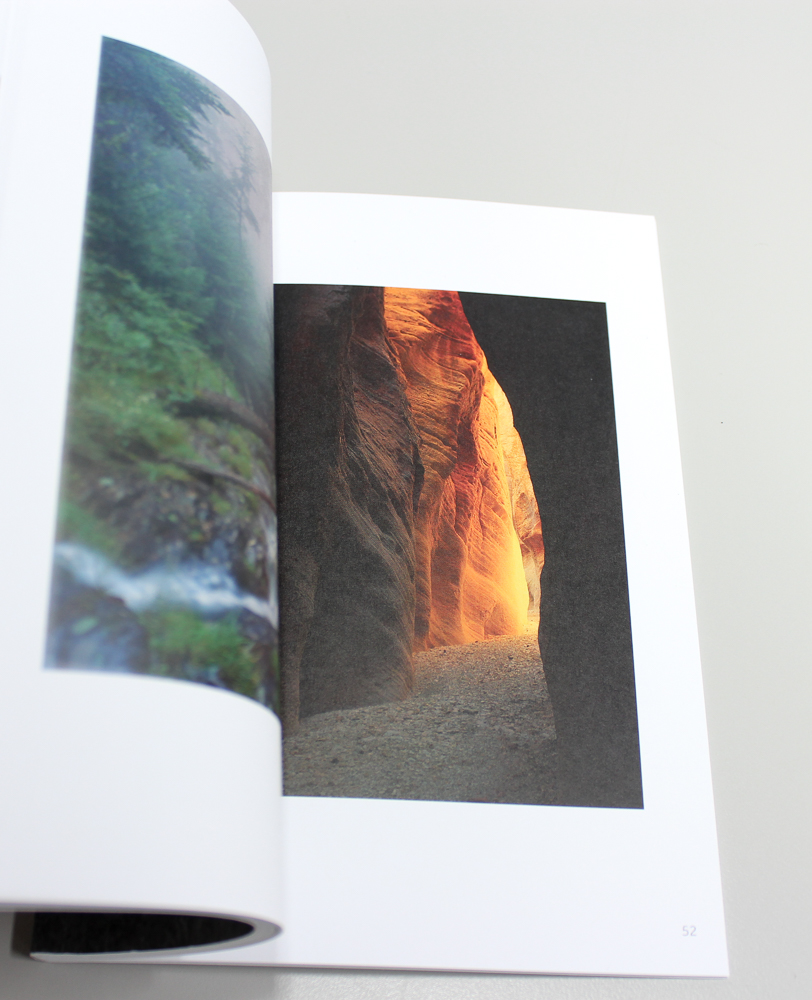

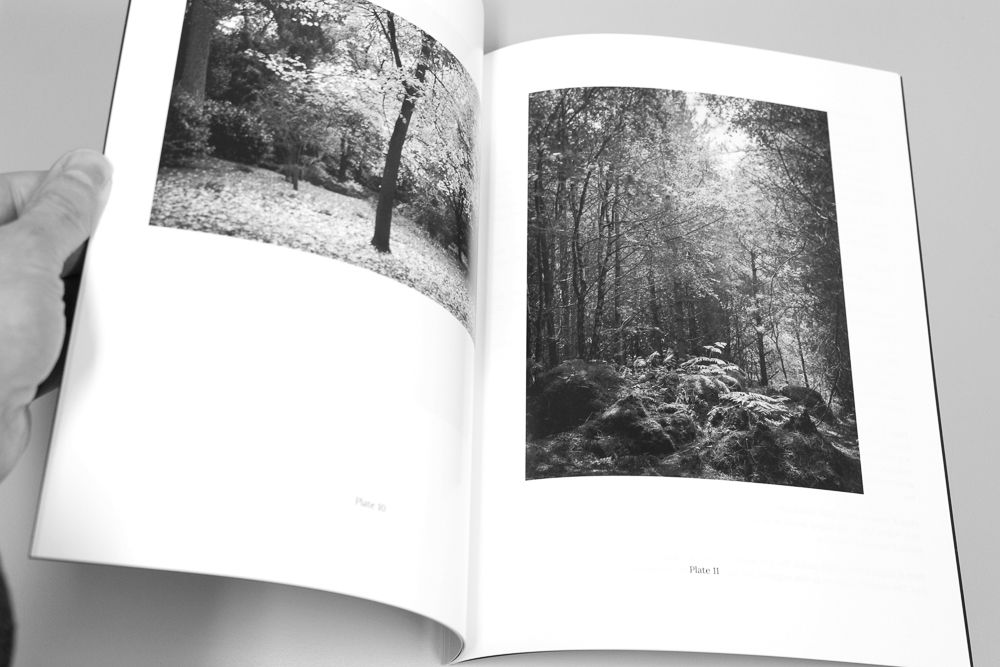

Trees and Woodlands Zine in Pictures

Trees and Woodlands Zine

Announcing my forthcoming mini-publication / zine, Trees and Woodlands.

This will ship in the new year, for a limited time period, as a gift to anyone who buys one of my prints. As the subtitle suggests, it contains eleven of my tree photographs, all shot on film. Additionally, there is a short introductory essay, technical notes for each shot (film type and so on), and a ‘hints and tips’ section on making effective woodland images. In hand, it feels like a slim magazine with good quality reproductions.

From today, the zine is also available in my shop as a modestly priced digital download. I recognise that not everyone may be in the market for a print, so it’s a good, economical way of making my zine more accessible.

@dsamaddar (Dev Samaddar)

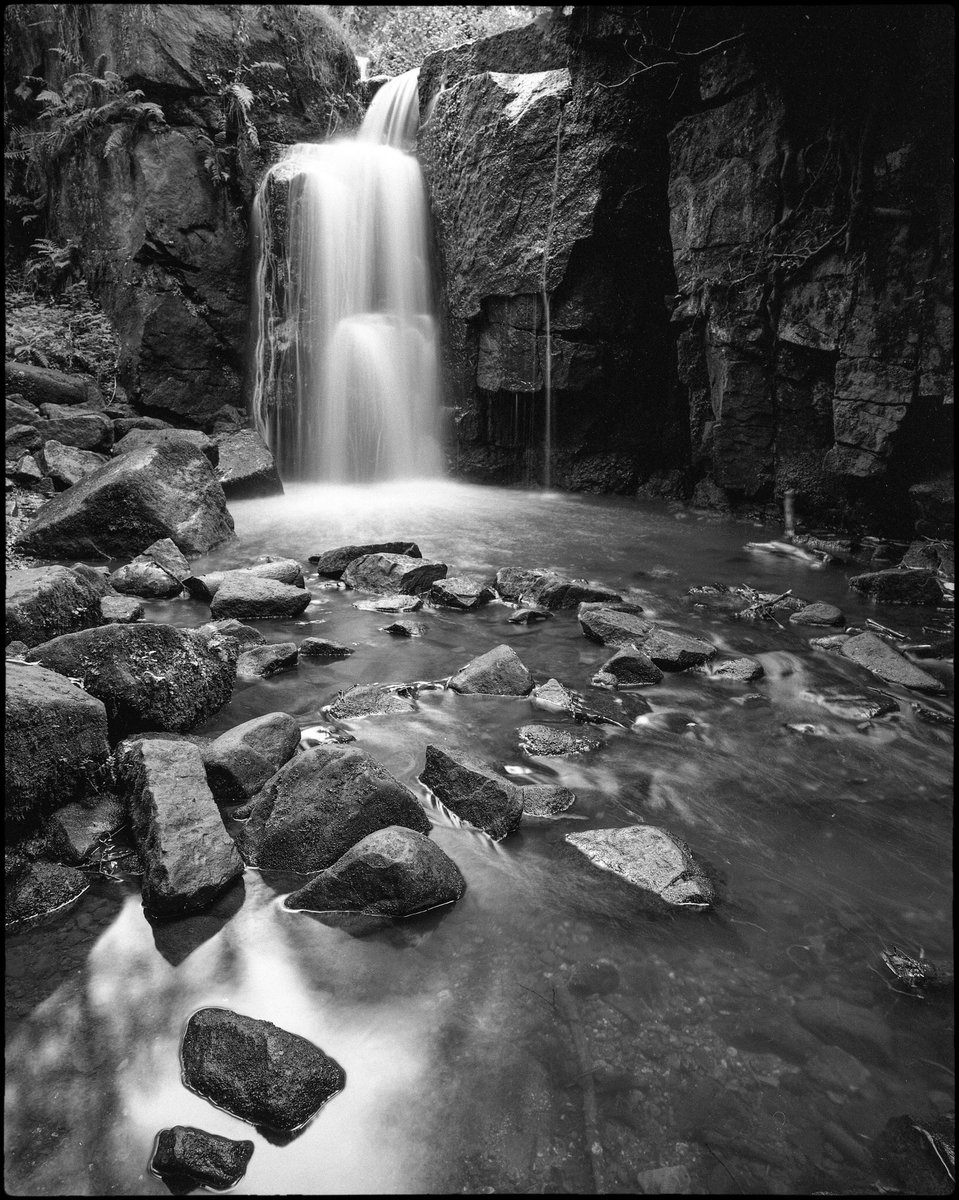

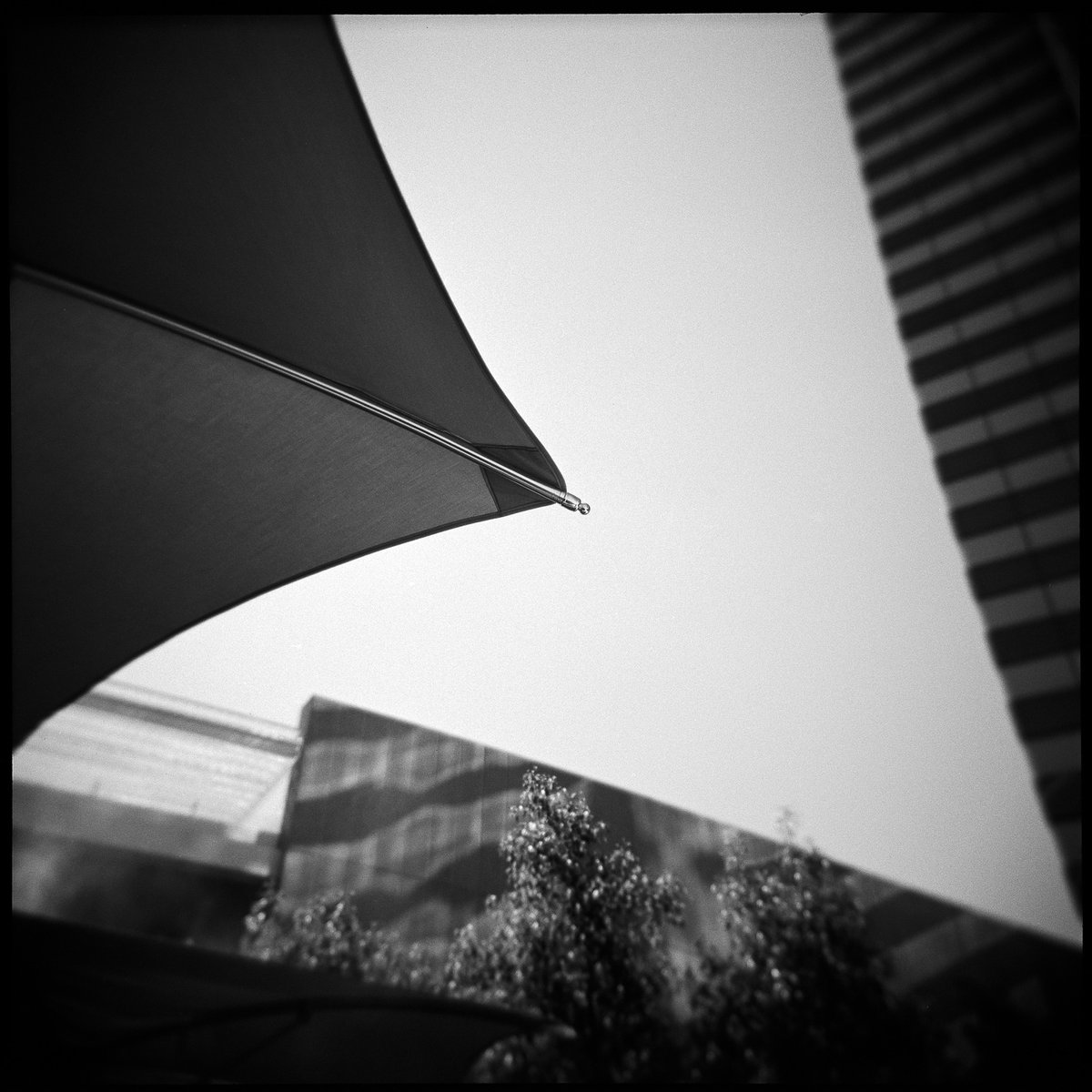

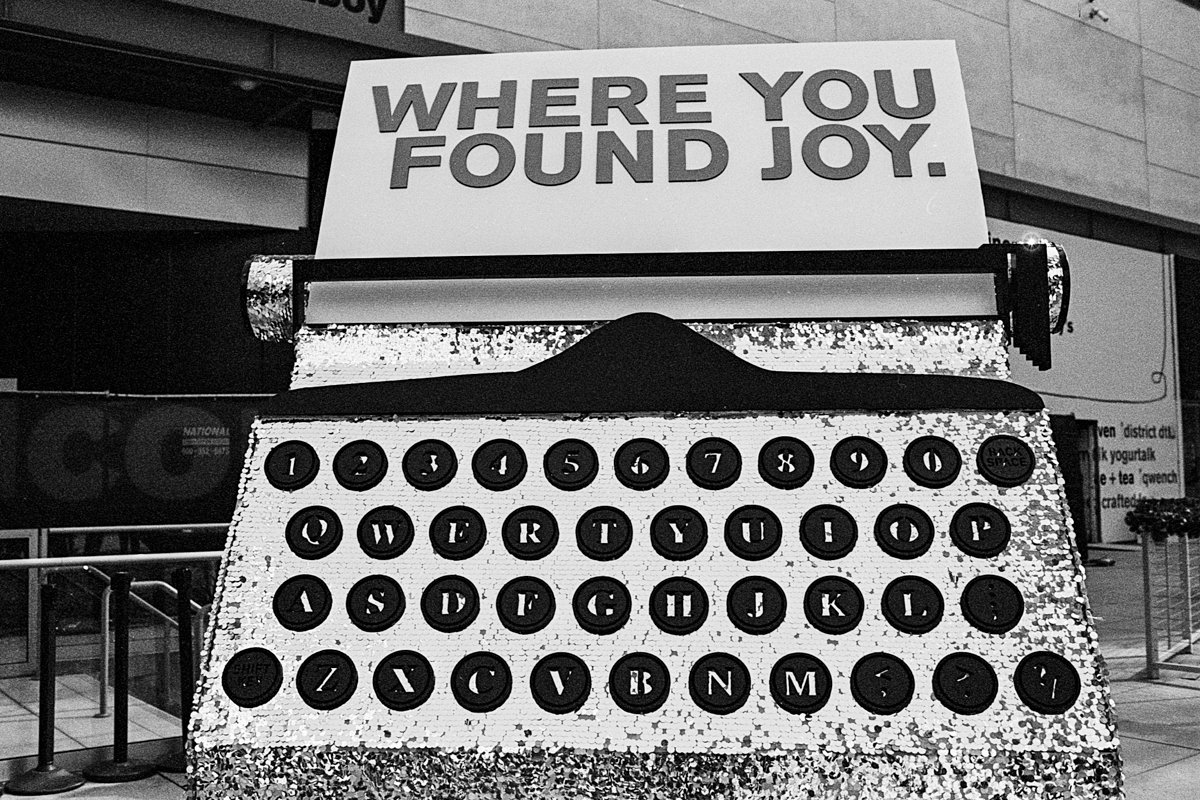

Can you say why you love black and white film in one image? The gallery (part 2)

I asked the question and the Twitter photography community answered.

I have already published ‘part one’ of this gallery (see the post here). Such was the quantity and quality of answers that I felt compelled to make a ‘part two’, and here it is.

I hope you enjoy these images as much as I did.

@mrdaveyoung, HP5 pushed two stops.

@dizd (Dizzy Cow)

@CanonF1 (Sergio Palazzi), FP4

@PanamStyle (Copyright Earl Dunbar)

@sammyzorba

@EMULSIVEfilm, Ashes to Dust, Eastman Double-X @ 1800

@lmstevensphoto

@nigel_roberson6

@chris1729 (Chris Wright)

@DrMarsRover (Monika)

@mellonicoley

@jasjitphoto

@JohnScarbro1

@emulsionkid (Zach Schroeder)

@Trend2signif (Dr Al Dav)

@Nebacul (Ben K)

@StuM35mm (Stu Myers)

@viewfinder_m6 (Adrian Taylor)

@196photo (David Walster)

@SilverPanLab, HP5 @ 1600 developed in Microphen.

@pixelsonapage (Barry P)

@AukjeKastelijn, Tri-X pushed two stops.

@ozalba (Duncan Waldron)

@thisJasonSelf

@TheFeelofFilm (Ellen Goodman)

Can you say why you love black and white film in one image? - The gallery (part 1)

The question is at once fertile and mischievous. Fertile because of the questions that it raises; mischievous because answering it is hopeless bordering on folly. As a black and white photographer, I know, to a point, why I like black and white film. I can begin to point to concrete things: grain, tonality, the gravitas of analogue, the philosophical frisson of the image imprint in silver. I can even come up with an image, or maybe two …. or of course more. Choosing but one is difficult.

So when I asked this question on Twitter recently, I sat back and watched the responses with pleasure. So many different, nay radically different, responses. I reminded myself that the photographers were trying to answer the question in just one image: this was ‘it’ for them, an essence, a core approach or love in a sea of possibilities.

Looking at the work, those other questions of which I write soon follow. Is it a black and white film portrait, or the person that is the object of the image maker’s interest? Is it that still life object rendered in film that seduces or is it still life on film more generally? Is it those streets / hills / trees on film or something more abstract again? Do we as viewers identify with black and white film first, or the genres of landscape, street, portraiture (and so on), and then film? Do we simply identify with the image because of its formal strengths, or because the making of it has some kind of significance (like the camera it was made on), or are there autobiographical factors (it was a happy time, a memory)? What role does the film stock play? Doubtless the answers are multi-faceted. All from that seemingly simple question.

Delighted by the response on Twitter, I decided to offer a home to the images. In fact, there are so many that I will be publishing a ‘part two’ in about a week’s time. I started out almost systematically trying to include all the responses to my original post, but the task became simply too big. So please find my humble attempt at a gallery below. It is doubtless coloured by my own eye, and has certainly been limited by the practicalities of contacting folks for image permissions and of putting it all together. Apologies if I’ve left you out, it is more by accident than design.

For simplicity, I have left the Twitter name to stand for the photographer’s name, especially where a proper name is legible from that. I’ve included proper names where it made sense to do so, and some photographers gave me more information (which I’ve added). Some people requested links to their sites (these are next to the names). If I have your name wrong, please get in touch and I’ll change it. The names of photographers published herein are also an assertion that the copyright of the image belongs to them.

I hope you enjoy seeing the images together like this (I certainly have), and please do look out for the gallery part two.

@AdamAnalogue

@NCMBianchi goshootit.net

@will_mallet

@carusb (Chris Rusbridge)

@RickKellerMD, Gravida, Cambo 4x5, Nikon 300mm f9, Ilford Delta 100

@Tinedo (Michael Zipser)

@SwoonTheMoon (Leah J)

@Givemeabiscuit (Sandeep Surmal)

@atlantean526 (David Henderson)

@DBloomsday (David S Allen)

@mparry1234 (Matt Parry)

@silentcar (Adam James)

@EugeneKCamera (Eugene Keogh)

@Hannah_forsyth, Kodak Tri-X

@JeremyCalow

@HenrySabio

@ntruj (Nick Trujillo)

@AndyClarkePhoto

@royfocke rofopho.de

@stevenelawson

@adiw1202 (Adi W)

@VintagePhotoCo (Rachel Brewster)

Can you say why you love black and white film in one image?

I asked this question on Twitter the other day and the response has been overwhelming.

So many interesting images were posted by way of reply, and I’ve begun to think they really deserve a home. I’m therefore going to create a gallery blog post, with a little modest commentary (like I did for #Treephotogallery).

If you replied with an image, I’d like your permission to include it in the post. Please send me a direct message on Twitter signalling your permission, or use the contact form on this website. If you have not yet submitted an image and want to, either reply to the original post or get in touch directly. Don’t forget to signal your permission for publication too.

The small print:

Participants agree to publication on this website, and therefore license me, without charge, free and unhindered use of their image. The copyright will of course remain with the photographer. I may not be able to use all images due to space (and time). If your work is not selected, please note this is not a verdict on your work. Naturally, my own eye and preferences will also be at work.

HP5 Plus exposed at 3200

I’ve been doing some experiments exposing Ilford HP5 Plus at 3200 for the grain. Here’s a trio for your perusal. You can see they are of flowers, shot on 35mm and close-up using an extension tube. The tendency towards abstraction, and areas of simple tone, emphasises the grain I think.

HP5 Plus exposed at 3200 developed in LC29 for 11 mins

HP5 Plus exposed at 3200 developed in LC29 for 11 mins

HP5 Plus exposed at 3200 developed in LC29 for 11 mins

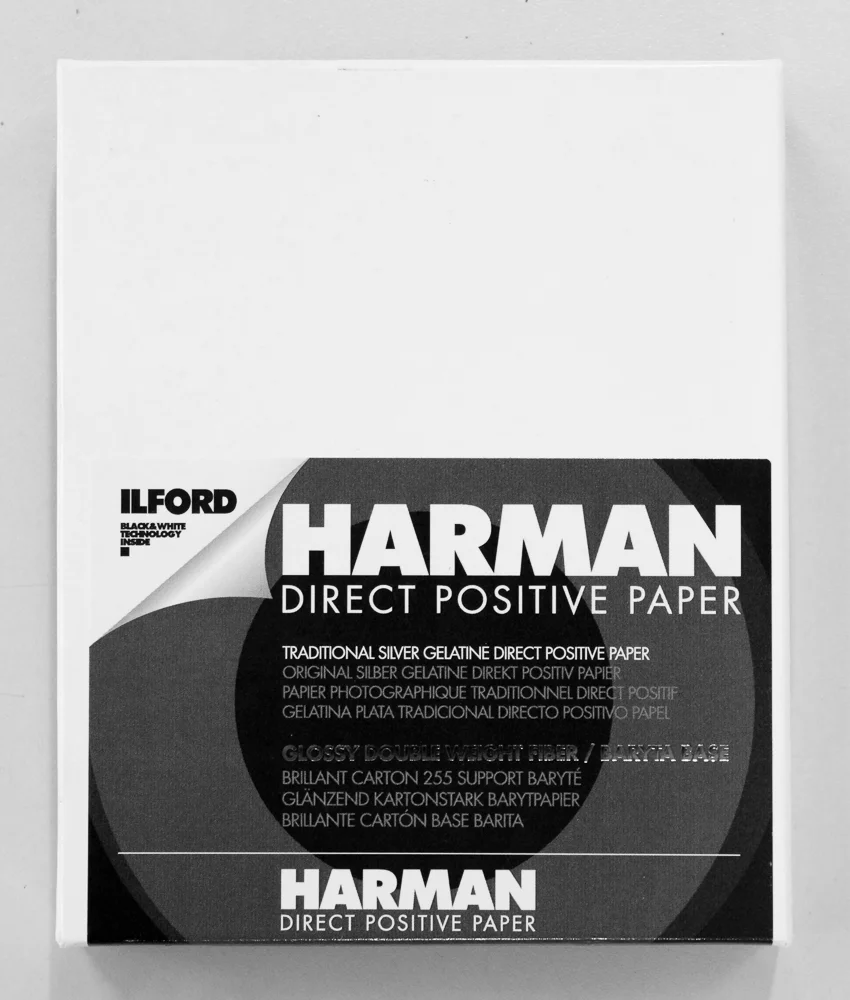

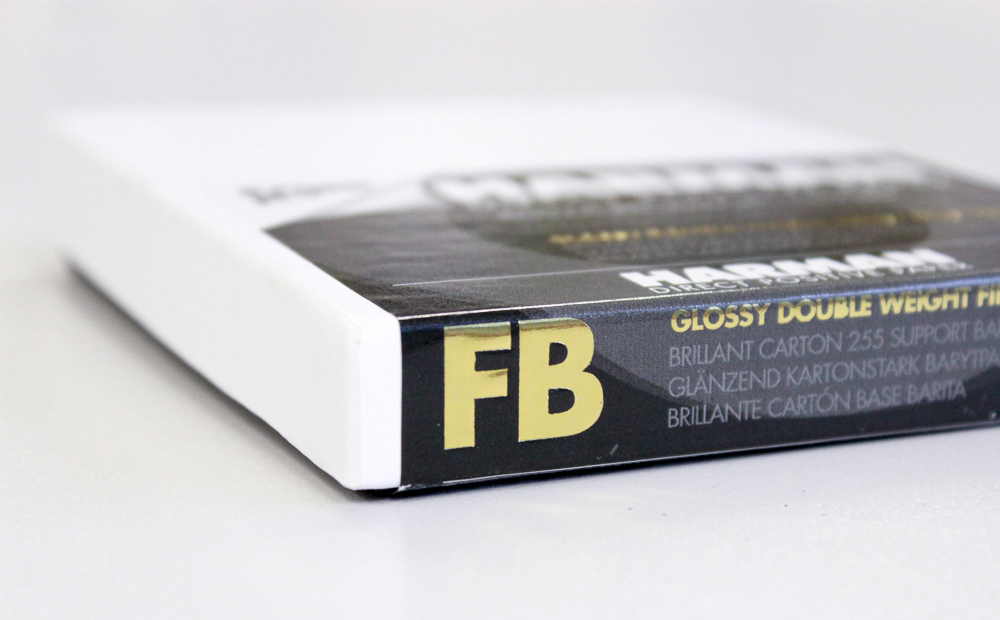

Harman Direct Positive Paper

Harman Direct Positive Paper is traditional fibre based paper with a special ability. When exposed to the light -- in a camera or pinhole camera -- it forms a positive image. This behaviour is precisely the opposite to that of standard darkroom paper, and is a boon for anyone seeking to make direct prints without the need for a negative, paper or otherwise.

I acquired a pack in 5x4” size last week and set about putting it through its paces. I worked in close proximity to the darkroom, which, as it turned out, was a sound decision. Moving from a still life setup to the darkroom and back again made getting a measure of the paper, of how it exposes, relatively easy. I made and corrected mistakes and began to see a glimpse of the delightful tonality the paper has to offer.

Paper is much slower than film and this paper is no different, being approximately ISO 1-3. This makes for relatively long exposures in all but the brightest conditions. Pinhole photographers will be familiar with this way of working (pinholes being very small apertures in themselves resulting in long exposures), but anyone wishing to use the paper in a conventional large format (or other) camera will have to weigh up the extra exposure time against their pictorial intentions. Sharp portraits, for instance, could well be a challenge for the sitter.

I resolved to test the paper in my trusty Intrepid Field Camera. My 150mm lens allows for relatively close focussing, albeit with significant bellows extension. The Intrepid was up to the task, and I was able to make the kind of floral composition I had in mind. The paper is luxuriously thick, as a baryta darkroom paper usually is, but this does provide a challenge to squeeze it into a film holder. At first I thought it might be a little too large in area, and so I trimmed the edges. This didn’t solve the issue, so the paper thickness certainly was to blame. Nevertheless it can be inserted with a little effort. Film holders are designed to hold film after all!

After some initial mistakes I began to make some pleasing images. An error I did make was to use window light. This surely added to the quality of light in the images, but as the winter day darkened I began to chase exposure changes and so made some errors. It didn’t help that sky also brightened intermittently.

A relatively high key image boasting a wide-ranging tonality, on Harman’s Direct Positive Paper.

The image shown above is a good representative sample of what the paper can do. I see a paper capable of subtle shifts in tonality that retains excellent detail. The paper is said to produce images of generous contrast, but I wouldn’t discount it for a wide and subtle tonal range. There is something exciting about making a one-off, original image in this manner. For sure, this may be precisely the reason some won’t like it, but if you enjoy alternative processes I wager you will.

I have waited some time to get hold of a box of this excellent product. Hopefully my getting hold of it means that it is becoming more available than it has been. If you’ve had your eye on it and haven’t so far been able to get any, now might be the time to look again. I don’t think you’ll be disappointed.

City of Birmingham, Oriental Seagull 400 in LC29 developer.

City of Birmingham

A 10x8 negative on Ilford HP5+, shot on my Intrepid Field Camera

Mulling over the negative

One of the pleasures of 10x8: taking one’s time.

And so I have been. Taking my time. Going slowly. Slow photography. 10x8 style.

This process invites contemplation; room for visualisation before action. So today I invite you to join me as I contemplate this negative, a neg I haven’t even contact-printed yet.

I exposed for a ‘pale’ image punctuated by the dark line of the traversing diagonal branch. I envisage that the rich foliage will offer a large range of tones, even at a lighter register. As ever, questions present themselves: will this be the case? Does the composition quite work? (The bank of foliage in the foreground is perhaps too large.) Will the darker diagonal look too incongruous against the lighter tones? Is there a greater tonal range than I envisage?

Here I feel at home with 10x8: a little work here, a little work there. It fits in with my schedule and my tendency to ponder. Perhaps before too long I’ll be sharing this piece in a more finished form.

The full negative on the lightbox.

The Intrepid 10x8 Field Camera in use.

Intrepid 10x8 Field Camera Review

I can remember my excitement when I first saw the Intrepid 10x8 Field Camera on Kickstarter. I was already very familiar with Intrepid’s 5x4 model (see my review earlier in this blog), so I felt like I knew what to expect. Yet this wasn’t 5x4, it was no ‘small’ format, it was 10x8! I started to dream of 10x8 contact prints, and felt like a little boy wishing for Christmas. It was a camera I had to have.

I duly paid my Kickstarter pledge and waited for the camera to arrive. When it came, I was immediately struck by its size. The size of cameras is of course relative, as in all things, and what may be considered large by one person in one context can be quite small in another. The 5x4 model was still fresh in my mind and hands, and it was this that began to look positively miniature by comparison. The 10x8 was a big piece of wood. It’s worth pursuing this notion of ‘largeness’, because it plays into operational considerations of weight and bulk. It’s an aspect that properly belongs in a review written for the would-be purchaser, such as this one.

The front standard with Intrepid's own lens board and logo detail.

The camera is made mainly from birch plywood with anodised metal elements. It has a front standard with swing and tilt movements, and there is some back tilt to the rear. There is a ground glass with gridlines and a beautiful etched ‘Intrepid Camera’ logo. On the top of the camera is a useful, small spirit level, and the camera is finished off with a large logo on the bottom. At the time of writing the camera is available to order in blue, black, green and red bellows. I opted for blue as I already had red in the 5x4. (I am happy with my choice, although I do rather admire the black from afar.)

On the ground glass is a beautiful etched logo. Someone has given a great deal of thought and love to this camera.

The logo on the base of the camera (with suggested destination).

There are those who are wary of plywood as the primary material, but I can’t say that I am one. There is a context here, which is the existing market for traditionally-made 10x8 cameras. There are some truly beautiful models out there, usually constructed from woods that would not be out of place in high quality furniture. These are highly precise, hand crafted cameras that last a very long time (witness the large format second-hand market). They also come at a premium. The raison d'ȇtre for the Intrepid large format models is affordable and lightweight. I have used my 5x4 quite extensively and see no deterioration in the wood. I therefore have no reason to think there will be issues with the plywood on my 10x8 in the near future. Long-term may be a different question, but you will see I refer my thinking to the important context.

The camera from the front, in the field.

Operationally, the 10x8 Intrepid is very similar to the 5x4. The camera folds to something like an 8 cm deep, one foot square for transportation. It therefore needs to be unfolded and the front and rear standards tightened into place when in use. This can be done quite quickly, and I found the 10x8 no longer to set up than the 5x4. The lens board is inserted in a similar manner, and the mechanism for holding it (a metal part with two screws) the same. Focus is by means of a knob underneath the front standard, and a parallel knob allows the lens to be secured in place once focus has been achieved.

The camera folded up. You can also see the small but useful spirit level.

There is one important difference however, and this is a product of the design of ground glass and film holder receptacle. When the camera is first unpacked, the ground glass is in portrait orientation. In the 5x4 model it can simply be turned into landscape mode, a very convenient feature made possible by clever design and the miracle of magnets. Magnets are still present in the 10x8 version, but now the user must unscrew the back, take it off, and screw it back on in the alternative orientation.

The rear of the camera in portrait orientation, with film holder inserted.

When I first looked at this I thought the design was elegant enough and didn’t pay it too much attention. I must say that having used it for a time in the field, it isn’t quite as smooth as I’d like. On my copy of the camera, some fiddling is required to marry the screws to their receiving holes. Not a big issue, but for someone like myself who likes to change from portrait to landscape frequently, a small hurdle to very smooth operation. Indeed, when I first used the camera I tended to forget that the back needed to be returned to the portrait orientation before the camera can be collapsed. You can’t close it if the back is left in landscape mode. A quirk that you learn for sure, but worthy of mention here.

A close up of the screw mechanism used to change the orientation of the ground glass. Not all 10x8 cameras can change orientation (i.e. some are fixed in either portrait or landscape), so there is an upside to this design, too.

The critical reviewer of cameras sometimes treads a fine line, especially with something like this wooden camera where there may be variations between samples. I only have the one camera, paid for by my own money, and so the reader should be warned that some of what I write may apply only to my specific example. At any rate, I know that Intrepid are extremely receptive to feedback and already have a sound track record for improving their products (the 5x4 is currently on its third iteration). I write in the spirit of critical feedback and ongoing improvement.

When I first received my camera, the focusing was not very smooth. I applied a little extra machine grease to the mechanism and ‘exercised’ it a few times to loosen it up. There is no doubt that it works fine (because I have tested it in the field), but I do still have the impression of the teeth ‘missing’, at certain points, as the focus is turned. Perhaps there is scope to add more precise metal parts to this area, which does have to move a large section of wood (by contrast the 5x4 moves a very small panel and the plastic parts have no problem at all in providing a very smooth operation).

When I made my first exposure I realised I had a light leak. At first I thought it was an issue in the darkroom, but then it struck me that the shape on my negative pointed to light inside the camera. A quick check with a torch in total darkness confirmed what I suspected, and I resolved the problem with a little glue on the bellows. I have had no light leaks since, but the incident taught me early on to check for leaks before any substantial expeditions. This is an element of good practice with large format, although Intrepid may wish to give thought in the long-run to how their bellows are attached. Perhaps a mechanism other than glue will exceed the brief and price-point of the camera, I don’t know. Again it’s worth stressing that I’m writing about my copy and other Intrepids may not see this issue.

It is important to scrutinise the camera, but now I must write of pleasures. Of the pleasures of 10x8 as a format and of using this simple, wonderful camera that looks good on the eye and even smells pleasant! There was more to my desire to shoot 10x8 than camera envy, or a wish for capricious change; I have long wanted to shoot 10x8 so that I could make contact prints. Readers of this blog will be familiar with my obsessions with the print, and indeed with the aesthetics of film, so what could be more attractive for me than the promise of a film format that could potentially deliver prints of the very highest order.

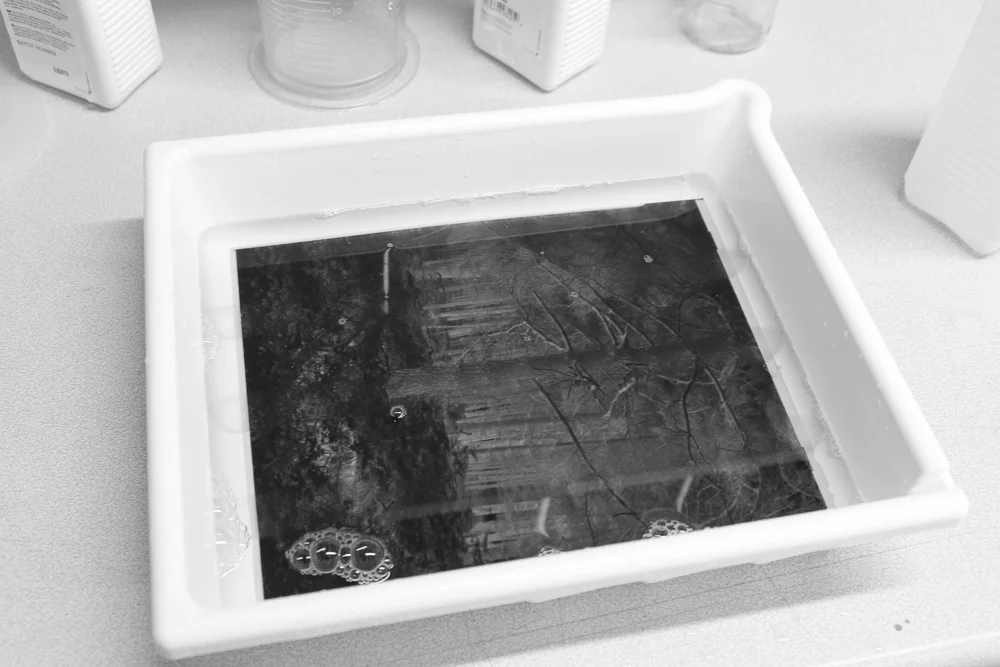

The joyous sight of a 10x8 contact print in the wash.

This review has been some time in the making because I wanted to spend time with the camera - and to spend time printing and actually making work. This I have done, and so I feel like I can write with some sound experience and insight. I have had a lot to learn beginning 10x8, and have learnt a lot. I don’t want to go too much into this here, because the danger is I will stray into writing about the format rather than the camera. However, some points are relevant, again because they speak to Intrepid’s brief and what I consider to be their success.

One of my 10x8 negatives receiving wetting agent.

If you are reading this review you may well have some sense of what might be required with 10x8, even if you have not yet tried it. 10x8 demands a commitment in planning, journeying, and physically carrying gear that other formats do not, and tolerates nothing less than impeccable craft. These are the source of its frustrations and its joys. When it is good, it is really good. Other than price, and therefore accessibility, the chief selling point of the Intrepid is its weight of 2.15 kg. A Chamonix 810V weighs 4.3 kg. (Although in fairness, they do produce a lightweight model, still heavier than the Intrepid at 2.46 kg.) I spent a long time searching for an appropriate bag / backpack (and my solution is worthy of review in its own right), but suffice it to say a good solution weighs 2kg itself. This makes a pack of roughly 4kg in weight with only a ‘standard’ focal length lens inside, and a large tripod to carry. As someone interested in landscape images, I have to wonder whether I could take 10x8 images at all with a traditional camera model. At any rate, some physical training and a re-evaluation of my sedentary ways may be in order.

The Intrepid packed away and ready for adventure.

When the Intrepid was first released there was a fair amount of discussion about its stability or lack thereof. I haven’t used the camera in any particularly challenging conditions, but I have made moderately long exposures outside and with some wind. My negatives show no evidence of camera shake. The front standard is very secure on my copy, and indeed I hadn’t thought to question its stability until I read the discussions. Perhaps for some users accustomed to heavier equipment, or who have need for longer exposures in adverse conditions, this may be more of a concern than it was to me. I am happy to report that I have made technically sound negatives with the camera, something on which I have been able to build (with no small excitement) in the darkroom.

The 10x8 format is well suited to the revealing the details of this majestic tree. Unfortunately this negative betrays an early processing mistake I made: witness the line down the right hand side from too-even tray agitation.

When I began printing, I had in mind the old adage that the harder the format is to shoot, the easier it is to print. There is a certain amount of truth in this, although I have come to look somewhat suspiciously on the oft touted idea that contact printing is more straightforward than conventional enlargement. You can see where the logic lies: gone is the enlarging stage, with its limitations of lens quality and potential dust contamination. Perhaps it is the legend of Edward Weston making beautiful prints with nothing more than a contact print maker and a humble bulb that prevails. In point of fact, I encountered several technical issues, dodging and burning can be quite a challenge on the scale and with the room afforded, dust still accrues, and my desire to make a borderless image on a larger sheet of paper necessitated hours of difficult trials with different masking solutions.

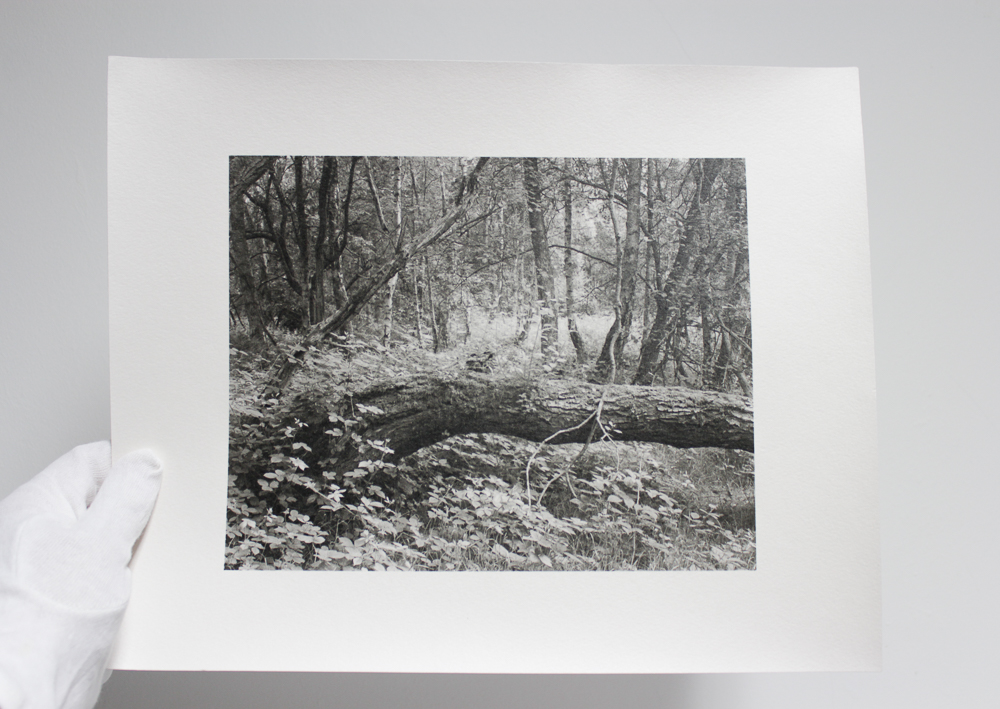

My Fallen Tree image on Ilford's sumptuous Multigrade Art darkroom paper. A version on fibre based warmtone paper is available in my shop at the time of writing.

Yet doubtless is the generous tonality and sheer visibility of the 10x8 negative. The Intrepid is a joy to compose and focus with, thanks to its bright and clear screen (limited however, it should be pointed, out by the maximum aperture of your lens). I felt I was much more in control of my image than I was with my 5x4 camera, simply because the flickering camera obscura projection is that much smaller on 5x4. This sense of control was magnified throughout the whole process: spot metering felt clearer and more decisive (I apply zone system control in processing for single images), negative inspection was a joy. I made but one studio portrait to see how the camera would function there, and the same advantages were apparent. I expect they would become even clearer with further use in the studio setting.

Hillside Tree, Somerset, Ilford HP5+ in LC29 developer.

I write this review today at a time when my 10x8 work has really started to get going. I have shared images made with the camera on social media and offered my first 10x8 darkroom print for sale on my website. I am thoroughly embroiled with this imperious format and it is in no small part thanks to the existence of Intrepid’s camera. Whether or not you have the money and inclination to buy a 10x8 Intrepid is of course your decision. Finances, circumstances and needs vary. Is the camera ‘affordable’ in the context of the large format camera market? Absolutely. Does the camera function properly and promise a proportional and sensible period of service to an industrious photographer. Without question. Is it a ‘way into’ 10x8 that I can recommend? Without hesitation.

The critical comments I have made herein are in the spirit of improvement. I offer my support to Intrepid because I like what they are trying to do and have benefited from their products in my own photography. The challenges of making affordable equipment in traditional photographic markets should not be underestimated. Witness Intrepid’s own attempts, and for the time being failure, to make a complementary affordable film holder. To paraphrase Intrepid themselves, here the company has discovered that there is a reason why some photographic equipment is traditionally so expensive. They simply couldn’t engineer a working holder at the price they envisaged.

I wouldn’t bet against them one day succeeding with the film holders. For now we have a fabulous camera and new photographic adventures to enjoy. I have to say, thanks to the Intrepid 10x8 Field Camera, this little boy’s Christmas has well and truly come early.

Fallen Tree. A 10 x8 contact print made on warmtone fibre based darkroom paper.

'Fallen Tree' Fibre Based Print

As part of my ongoing work with my 10x8 camera, I'm happy to offer for sale 'Fallen Tree' as a darkroom print. I have made a very limited number of contact prints from the 10 x 8 negative, on Ilford's Warmtone Fibre Based paper. The image size is a little smaller than 10 x8, and the paper size is nearly 11 x 14 inches. This allows the print to be mounted with a paper border showing, should the buyer wish. As always, the screen image fails to do the print justice, which really needs to be seen in person to be fully appreciated.